Cures and Curses offers an extensive look into the controversial history of pharmaceutical advertising in the United States. The exhibit consists of digital reproductions of trade card advertisements for patent medicine products from the 19th and early 20th centuries. The rise and eventual decline of patent medicines raise important questions about patients' rights, health literacy, pharmaceutical information ethics, and the responsibilities of medical practitioners.

Explore the impact of patent medicines on American public health, the influence of pharmaceutical advertising, and the use of controversial drug substances.

This exhibit was curated and created by Matthew Chase, San Marcos Campus Librarian.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Gallery

Patent Medicines

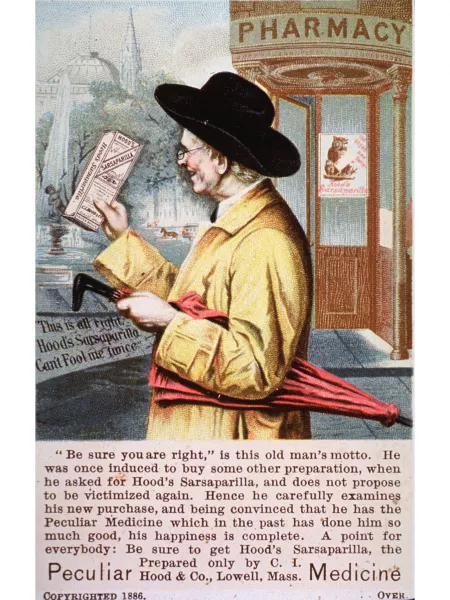

Patent medicines are commercial pharmaceutical products created and sold directly to the individual for self-medication. The term "patent medicine" traces back to the European legal practice of letters patent, which involved a sovereign ruler conferring monopoly privileges to an individual. The practice ultimately led to the modern patent system in the United States, allowing for pharmaceutical manufacturers to be granted patents for their remedies. Yet patent medicines that populated the U.S. economy of the 19th century were rarely ever granted such patents. It was instead a popular misconception among the public that allowed for the label to stick onto these proprietary medicines. The label provided an implicit legitimacy, adding to the historical popularity for patent medicines and the resulting commercial success. Patent medicines had come in a variety of shapes and forms. Products ranged in everything from tonics and tablets to bitters and sodas. The singular commonality among most patent medicines concerned their status as medicinal panaceas or miracle cure-alls, with pharmaceutical manufacturers claiming their remedies could treat an array of physical and mental diseases disorders and ailments.

Patent medicines in the United States dates back to before the Revolutionary War. American pharmacists relied heavily on the import of British patent medicine products. Shortly after the war, U.S. manufacturers started producing their own pharmaceutical products, with an increasing demand among apothecaries and hospitals. Still, the early days of American patent medicines were marked by a history of ill reputation, as the traveling peddlers of the products were often seen as con artists and scammers with quack remedies.

.png) After the American Civil War, American pharmaceuticals boomed with the introduction of mass production and industrialization, transforming the patent medicine landscape across the world. The innovative use of advertising technologies and techniques enabled these manufacturers to dramatically transform their public image as entrepreneurs of great sophistication. The patent medicine industry became highly regarded by the 19th century, reimagined as a respectable and cheaper alternative to traditional medicine. By 1906, an estimated 50,000 patent medicines were being made and sold in the United States. The public would seek out patent medicines due to promises of curing their afflictions, especially if no such hope was offered by traditional doctors. Members of the U.S. working class were particularly skeptical of the help offered by traditional medicine, or otherwise could not afford the treatment, turning to patent medicines as an alternative. Many patients in the 19th-century United States would often seek out patent medicines in addition to traditional western medicine and folk remedies. The advertising for these medicines alone became a multi-million enterprise.

After the American Civil War, American pharmaceuticals boomed with the introduction of mass production and industrialization, transforming the patent medicine landscape across the world. The innovative use of advertising technologies and techniques enabled these manufacturers to dramatically transform their public image as entrepreneurs of great sophistication. The patent medicine industry became highly regarded by the 19th century, reimagined as a respectable and cheaper alternative to traditional medicine. By 1906, an estimated 50,000 patent medicines were being made and sold in the United States. The public would seek out patent medicines due to promises of curing their afflictions, especially if no such hope was offered by traditional doctors. Members of the U.S. working class were particularly skeptical of the help offered by traditional medicine, or otherwise could not afford the treatment, turning to patent medicines as an alternative. Many patients in the 19th-century United States would often seek out patent medicines in addition to traditional western medicine and folk remedies. The advertising for these medicines alone became a multi-million enterprise.

Due to lack of government regulations, the formulas and recipes to make them were typically kept secret. It was very common for these often cheap patent medicines to contain potentially dangerous ingredients such as alcohol, cocaine, or morphine. Many proved to be harmless and ineffective ultimately, with the main ingredient often being water. Some patent medicines benefited some amount of symptom relief, such as headaches, which further reinforced their use. The placebo effect and self-diagnosis may have also been factors in their historical popularity.

It is important to note that patent medicines existed during a time in U.S. history when drug prescriptions from medical practitioners did not operate as we understand them today. It was not until the mid- to late-19th century when state laws allowed physicians to prescribe drugs to their patients. Yet the prescription was not required, which meant that patients could bypass their physician and purchase any pharmaceutical product, including patent medicines. It was typically much cheaper to acquire treatment from a patent medicine rather than treatment from a medical professional, although many doctors actively dispensed these proprietary medicines to their patients directly.

By 1931, an investigative report from the Committee on the Costs of Medical Care showed that patent medicines amounted to 10% of all expenditures on medical services and commodities among Americans.

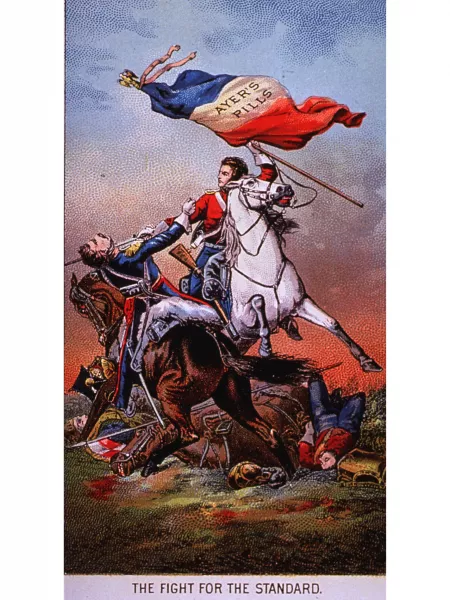

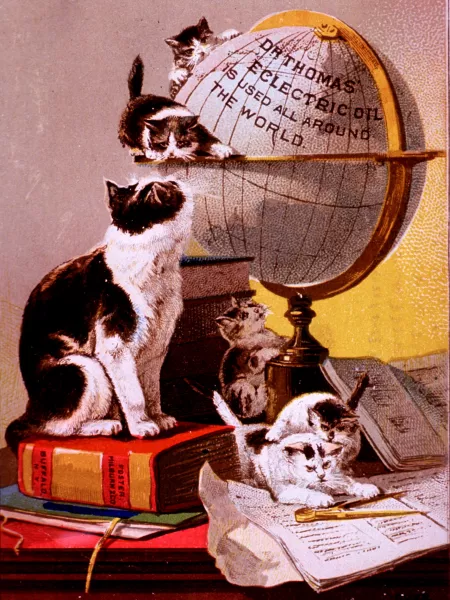

Power of Pharmaceutical Advertising

The boom of the U.S. pharmaceutical industry not only paralleled that of the U.S. advertising industry, the two were deeply intertwined. As patent medicines grew rapidly popularly among the American public, manufacturers invested increasingly more funding into their advertisements. Like patent medicines, U.S. advertising in its inception had been a widely stigmatized enterprise in society, undergoing a rapid transformation into the major facet of the American and even global economy that we see today. By the early 20th century, advertising had become a multimillion-dollar market.

There were no clear regulations on the manufacturing and advertising practices for patent medicines during the 19th century. Drug firms could voluntarily opt to observe the American Medical Association Code of Ethics, which stipulated that firms should only sell and market their wares to the medical professions, rather than the general public. Because this was a voluntary option, very few patent medicine manufacturers actually followed the AMA Code of Ethics. Patent medicine manufacturers pioneered modern American advertising, which we can continue to see today in both pharmaceuticals and other commercial markets.

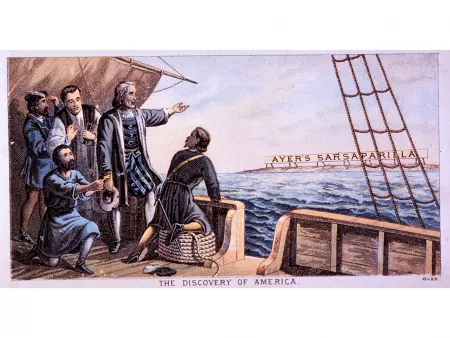

The public was exposed to patent medicine marketing everywhere from newspapers and magazines to calendars to even cookbooks. Advertisements could be found on horse carriages, walls, trees, and mountainsides. Traveling medicine shows were a common form of advertisement in the guise of entertainment. Newspapers relied heavily on patent medicine advertisements during the 19th century, amounting to approximately half of their entire advertising income. Patent medicine advertisements used the general public’s fears, hopes, prejudices, and other emotions and needs. Many ads would play on fears of death, disease, and suffering; exaggerating normal physiological phenomena as ominous signs of illness. Patent medicine manufacturers would also use sex, patriotism, and celebrities to sell their products.

The lack of marketing regulations allowed manufacturers to make exaggerated and even fraudulent claims about the potency of their medicines, offering them as universal cure-alls for anything from heart disease to tuberculosis to malaria. They often omitted information about the potentially dangerous ingredients such as morphine, alcohol, and cocaine. At the turn of the 20th century, many in the medical community, the media, and policy makers would come to criticize the abusive advertising practices, which ultimately led to the creation of the Food and Drug Administration to protect consumers and patients.

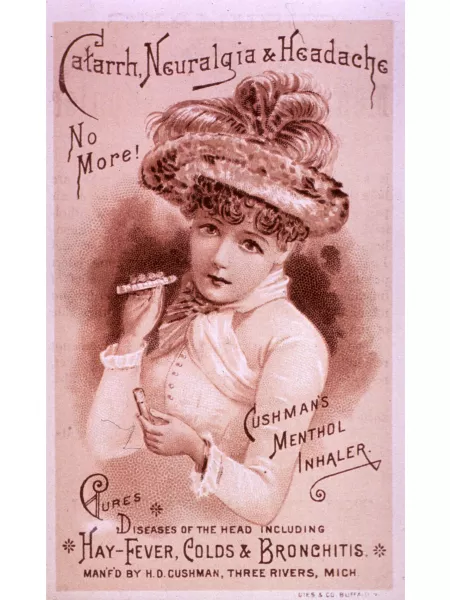

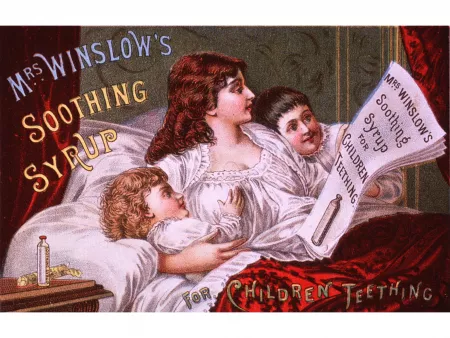

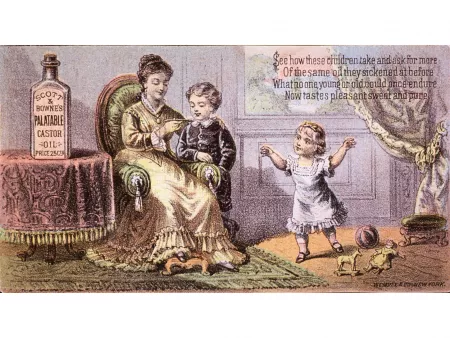

Women in Pharmaceutical Advertising

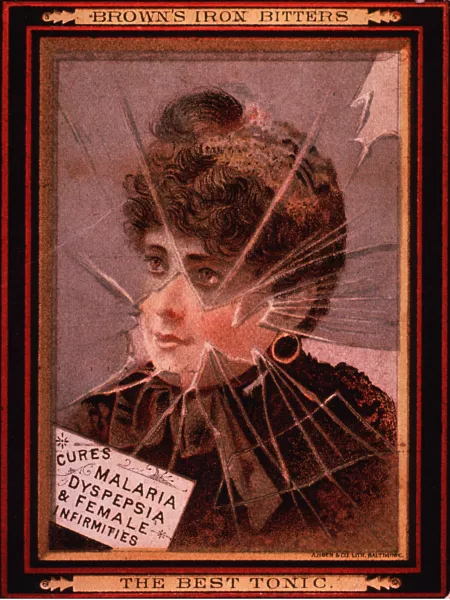

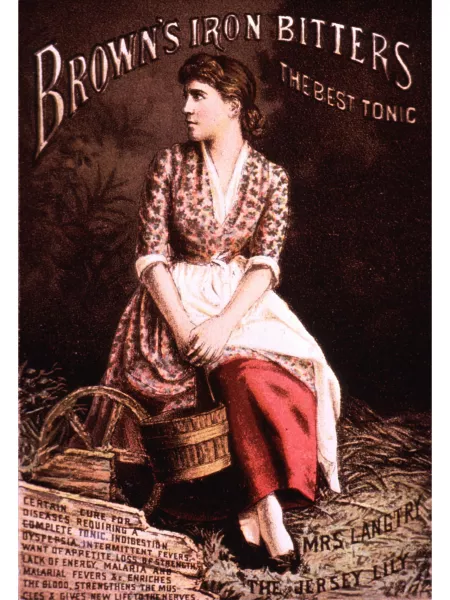

.png) The American woman of the 19th and early 20 centuries was commonly imagined as sickly and invalid. Sickness ran parallel to a woman’s femininity and beauty, with the prevalent belief of woman having delicate constitutions and emotional sensitivities. It is important to note that this American imagining of women particularly focused on white, middle-class women. Women of color and working-class women were seldom regarded as “proper” women. It should be no surprise then to see how the patent medicine industry dedicated most of their advertising to these white middle-class and upper-middle-class women, with marketing imagery that exploited these sexist sentiments.

The American woman of the 19th and early 20 centuries was commonly imagined as sickly and invalid. Sickness ran parallel to a woman’s femininity and beauty, with the prevalent belief of woman having delicate constitutions and emotional sensitivities. It is important to note that this American imagining of women particularly focused on white, middle-class women. Women of color and working-class women were seldom regarded as “proper” women. It should be no surprise then to see how the patent medicine industry dedicated most of their advertising to these white middle-class and upper-middle-class women, with marketing imagery that exploited these sexist sentiments.

Many advertisements would characterize women as long suffering, with alleged testimonials of women attesting to the medicine’s effectiveness at curing their complaints. The ads would reinforce existing medical thought that argued women’s illness to be essential or inherent to their inferior gender and physiology. Advertising campaigns exploited the medical pathologizing of women’s puberty, menstruation, and menopause as sicknesses to be cured (namely by the advertised products).

.png) Advertisers employed the medical professions to further legitimize their claims, not only in the medically accepted diagnosis that womanhood was pathological, but also in reaffirming women’s anxieties about their doctors’ ability to treat them effectively. Many women resorted to patent medicines due to this skepticism of medical professionals as well as the comparably cheaper expenses of using patent medicines to find relief. Anti-feminist advertising was commonplace, especially in the context of women’s increasing demand and involvement in social reform. Ads would typically draw causal connections between “unfeminine” behaviors (e.g., career ambitions) and physical sickness, implicate the alleged dangers of women’s higher education, and promote the virtues of marriage and the domestic life.

Advertisers employed the medical professions to further legitimize their claims, not only in the medically accepted diagnosis that womanhood was pathological, but also in reaffirming women’s anxieties about their doctors’ ability to treat them effectively. Many women resorted to patent medicines due to this skepticism of medical professionals as well as the comparably cheaper expenses of using patent medicines to find relief. Anti-feminist advertising was commonplace, especially in the context of women’s increasing demand and involvement in social reform. Ads would typically draw causal connections between “unfeminine” behaviors (e.g., career ambitions) and physical sickness, implicate the alleged dangers of women’s higher education, and promote the virtues of marriage and the domestic life.

Cocaine: Sacred or Scourge?

Cocaine has a long and global history in medicine, spanning more than a thousand years. Indigenous communities in South America use the coca plant traditionally for rejuvenation and stimulation, alleviating hunger, and treating altitude sickness. Cocaine became a popular medicinal panacea or cure-all in 19th-century western society, strongly supported by the clinical community and notably by Sigmund Freud. U.S. patent medicine manufacturers seized the opportunity to promote typically small amounts of cocaine in their products, particularly for headaches, neuralgia, and depression. The Coca Cola company emerged in the market as a cocaine-enriched “intellectual beverage and temperance drink” during Prohibition America.

Despite growing scientific evidence showing the addictive properties of cocaine, the drug became widely popular for recreational use in the Western world. Cocaine abuse resulted in thousands of deaths each year in 19th and early 20th century United States. Mounting negative public and media perceptions against cocaine, labeled as “third scourge on humanity,” changed how the drug was regulated at the turn of the 20th century. It was not until the Harrison Narcotics Act of 1914 that patent medicines were prohibited from including cocaine as an ingredient. Alternative compounds such as amphetamine would also come to replace cocaine as a western medicine, although it is still sometimes used as a local anesthetic. Cocaine’s status as a traditional medicinal compound became overshadowed by moral panics as a modern misclassified narcotic.

Race in Pharmaceutical Advertising

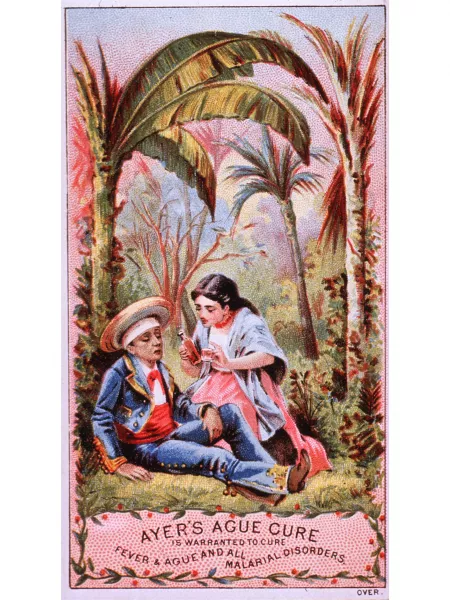

Racial imagery played a significant role in the history of pharmaceutical advertising, particularly when it came to patent medicines of the 19th and early 20th century. While patent medicines were primarily marketed to white middle-class men and women, race was exploited to reaffirm not only the public’s racist attitudes and social inequalities, but also the manufacturers’ sales in the process.

.png) Many manufacturers would use imagery of the exotic to sell their products, relying on the appeal of ancient times and mystical foreign lands. The name of the patent medicine was a popular way to demonstrate the exotic such as Mexican Mustang Liniment or Dr. Drake’s Canton Chinese Hair Cream. Other advertisements made false claims about the origins of their product. For example, the manufacturer of Dr. M.S. Watson’s Great Invincible Birghami Stiff Joint Panacea claimed the product had been discovered at the Nile River.

Many manufacturers would use imagery of the exotic to sell their products, relying on the appeal of ancient times and mystical foreign lands. The name of the patent medicine was a popular way to demonstrate the exotic such as Mexican Mustang Liniment or Dr. Drake’s Canton Chinese Hair Cream. Other advertisements made false claims about the origins of their product. For example, the manufacturer of Dr. M.S. Watson’s Great Invincible Birghami Stiff Joint Panacea claimed the product had been discovered at the Nile River.

Native Americans were a common source of advertisement imagery. The Kickapoo Indian Medicine Company advertised their products as made by “wise medicine men” on a Kickapoo reservation, when in reality, the company was led by two white Americans seeking to capitalize on the racial imagery. Many manufacturers marketed their products as “Indian,” fabricating the history behind their products as deriving from indigenous knowledge and traditions. The imagery served to not only conjure additional legitimacy to these patent medicines as part of indigenous authority, but it also reinforced the modern sensibilities of the white consumer. The Native American became a ubiquitous symbol in patent medicine advertising, with indigenous faces and identities being appropriated for the profit of predominately white manufacturers.

Traveling medicine shows relied a great deal on the advertising value of racial imagery, particularly in term of ethnic caricature performances. The use of blackface and redface in show performances was prevalent, framing the advertised patent medicines as representative of the exotic and nostalgic, bolstering a sense of (white) American superiority. These performances would reinforce the false claims of the product by stirring racial anxieties and tensions among white audiences in regard to their perceived physical, sexual, and mental inadequacies.

Despite the prevalent application of racial imagery in patent medicine advertising, many people of color became frequent consumers of patent medicines, although for largely different reasons than their white counterparts. Under the Jim Crow laws, black communities faced a lack of equitable access to healthcare and were skeptical of white medical practitioners. Black practitioners were few and often overwhelmed, leading many within the communities to seek out patent medicines. The advertised "folk-remedy" properties of these medicines appealed to black consumers as an alternative to traditional western medicine.

Race has had a complicated role in pharmaceuticals. We would later see race being used to support the nation’s first anti-drug laws; laws that came about in large part due to rampant patent medicine abuses and marketing practices. Prohibitions of common patent medicine ingredients would be espoused and enforced with racial imagery. Opium was associated with Chinese immigrants, alcohol with Native Americans, marijuana with Mexican immigrants, and cocaine with blacks.

'Non-intoxicating': Medicinal Use of Alcohol

.png) In 19th- and early 20th-century United States, alcohol had been a very popular household remedy, recommended and administered by physicians, for both children and adults. With the rise of patent medicines, alcohol became a common ingredient. Patent medicine manufacturers would often advertise their products as non-alcoholic despite having copious amounts of the ingredient. Many of these medicines had stronger alcohol content than beer, wine, and even whiskey, which helped to bolster their popularity.

In 19th- and early 20th-century United States, alcohol had been a very popular household remedy, recommended and administered by physicians, for both children and adults. With the rise of patent medicines, alcohol became a common ingredient. Patent medicine manufacturers would often advertise their products as non-alcoholic despite having copious amounts of the ingredient. Many of these medicines had stronger alcohol content than beer, wine, and even whiskey, which helped to bolster their popularity.

- Colden’s Liquid Beef Tonic (advertised to treat alcoholism) - 26.5% ABV

- Whiskol (advertised as non-intoxicating stimulant) - 28.2% ABV

- Howe’s Arabian Tonic (advertised as not a rum drink) - 13.2% ABV

- Parker’s Tonic (advertised as purely vegetable) - 41.6% ABV

- Kaufman’s Sulphur Bitters (advertised as having no alcohol) - 20.5% ABV

- Schneck’s Seaweed Tonic (advertised as entirely harmless) - 19.5% ABV

Medical Marijuana

Like cocaine, the medicinal origins of cannabis reach far in history, going back as far back as 5,000 years in Romania, India, and even Ancient Greece. It is no surprise then to find the drug as a popular ingredient in patent medicines of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Marijuana first emerged in the patent medicine world in 1850. The drug was marketed as a panacea, but particularly effective for headaches, pain, and neuralgia. Physicians and medical community leaders heavily invested in the clinical use of marijuana.

Following the turn of the 20th century, the public use of medicinal marijuana waned. The Marijuana Tax Act of 1937 served as the first time that marijuana became a federally restricted substance, with increasing criminalization in the decades following, leading up to the prohibition of marijuana under the Controlled Substances Act of 1970. The restrictions faced protest from the medical professions, although to no avail.

Anti-marijuana legislation and political movements would often employ racist rhetoric, associating Latino immigrants with the recreational abuse of marijuana and violent crime. This shift in marijuana’s status from being medicinal to criminal also greatly limited the scientific research of the drug, as the procurement of cannabis for academic purposes became restricted. Despite the resurgence of medical marijuana in recent decades, the drug is more commonly associated with counterculture movements and psychedelic aesthetics rather than its much deeper history as a medicinal aid.

.png)

.png)